Certain narratives, such as scientific texts, official reports or legal documents demand accuracy and, clearly, the ability to provide accurate description is essential, but the reader of fiction needs to be lured into a world that does not stop at reporting things as they are. Fiction needs to entertain and inspire. And so language strays into the figurative, the poetic, the lateral, the emotive. The author seeks to take advantage of the readers’ experiences, and, to achieve this, literal description can be quite inadequate. So comparison is used. Do you remember in school … as cold as ice … as black as night … as deaf as a doorpost (!).

Certain narratives, such as scientific texts, official reports or legal documents demand accuracy and, clearly, the ability to provide accurate description is essential, but the reader of fiction needs to be lured into a world that does not stop at reporting things as they are. Fiction needs to entertain and inspire. And so language strays into the figurative, the poetic, the lateral, the emotive. The author seeks to take advantage of the readers’ experiences, and, to achieve this, literal description can be quite inadequate. So comparison is used. Do you remember in school … as cold as ice … as black as night … as deaf as a doorpost (!).

Simile. It’s useful in description. It’s a way of relating one thing to something else, using the features of a known thing to describe the new thing. But simile also includes the ‘like’ comparisons and can involve actions as well as objects:

‘A hot wind was blowing around my head, the strands of my hair lifting and swirling in it, like ink spilled in water. (Margaret Atwood, The Blind Assassin)

‘… though he was a big man, he moved as softly as if all his shoes had soles of velvet, as if his footfall turned the carpet into snow.’ (Angela Carter, The Bloody Chamber and Other Stories)

Hum, not just straightforward simile. And beyond simple simile, there’s metaphor. Whereas simile likens one object or action to another, metaphor presents one object or action as being another, setting it in a different context for descriptive purposes:

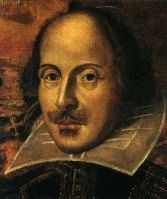

‘… and Juliet is the sun. Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon …’ (William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet)

‘He sailed through his exams’

Metaphor pervades our language: the slippery slope … the rat race … the information superhighway … kicked the bucket (idiom) … black sheep of the family … affairs of the heart (not the organ actually associated with emotion) … life’s journey … books are the mirrors of the soul (Virginia Woolf) … I was over the moon, Brian (metaphor plus sport hyperbole). As with simile, metaphor relies upon comparison, offers analogy, presenting one thing as standing in for another, highlighting a connotation or establishing a connection, causing things that are different to become the same. It adds another layer of meaning to a description and makes a reader work harder to create a clearer picture of the thing or action being described. It appeals directly to a reader’s experiences via implied or implicit similarities but it also makes greater demands on the imagination, using non-literal comparisons, often to achieve a rhetorical effect.

… black sheep of the family … affairs of the heart (not the organ actually associated with emotion) … life’s journey … books are the mirrors of the soul (Virginia Woolf) … I was over the moon, Brian (metaphor plus sport hyperbole). As with simile, metaphor relies upon comparison, offers analogy, presenting one thing as standing in for another, highlighting a connotation or establishing a connection, causing things that are different to become the same. It adds another layer of meaning to a description and makes a reader work harder to create a clearer picture of the thing or action being described. It appeals directly to a reader’s experiences via implied or implicit similarities but it also makes greater demands on the imagination, using non-literal comparisons, often to achieve a rhetorical effect.

In literature, extended or sustained metaphor is often used to prolong the association between two unrelated objects or ideas for literary effect. The metaphor continues through several sentences, several paragraphs, even an entire work. In As You Like It, Shakespeare introduces and sustains a world-life-stage metaphor:

In literature, extended or sustained metaphor is often used to prolong the association between two unrelated objects or ideas for literary effect. The metaphor continues through several sentences, several paragraphs, even an entire work. In As You Like It, Shakespeare introduces and sustains a world-life-stage metaphor:

‘All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players; They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts. His acts being seven ages … And so he plays his part …’

It was later reworked by Truman Capote:

‘Life is a moderately good play with a badly written third act.’

Shakespeare frequently employed extended metaphor. In Sonnet 18 he goes so far as to declare his intended comparison:

‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate … Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimmed … But thy eternal summer shall not fade …’

Incidentally, this piece contains what might be referred to as nested metaphor: ‘the eye of heaven’ refers to the sun to which the poet likens his lover.

More recently, Ian McEwan and Angela Carter’s works are also rife with metaphor. For instance, in The Child in Time McEwan dwells upon the theme of time, embedding an overarching temporal metaphor within the narrative, whereby the abduction and loss of the child becomes a metaphor for his main protagonist’s lost youth. In The Company of Wolves, Carter’s modern version of Little Red Riding Hood the metaphor of female empowerment is sustained throughout the entire narrative, culminating in Little Red’s taming of the conniving Wolf-Man.

Carter’s use of figurative language is always magnificent and I take every opportunity to quote this metaphor-rich paragraph from The Bloody Chamber:

Carter’s use of figurative language is always magnificent and I take every opportunity to quote this metaphor-rich paragraph from The Bloody Chamber:

‘I hid behind my furs as if they were a system of soft shields … And we drove towards the widening dawn, that now streaked half the sky with a wintry bouquet of pink of roses, orange of tiger-lilies, as if my husband had ordered me a sky from a florist. The day broke around me like a cool dream.’

The inclusion of metaphor in a text has long been acknowledged as an indication of the literariness and both McEwan and Carter are revered as literary authors due to their sophisticated use of this literary trope. The success of their figurative language depends upon the fact that it is anything but obscure. We recognise their literary devices and appreciate them. But some ‘dead’ metaphors are so deeply embedded in our language that we fail to notice them, for instance the conceptual or overarching metaphor which sees debate or argument as war … he won the argument … he fought to bring her round to his way of thinking … I tried to argue against it but he beat me down with his impeccable logic. (see Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1981). Metaphors We Live By)

In a nutshell, simile and metaphor are literary devices used to enhance description. But not all metaphors improve a narrative. Metaphors can be bad, inappropriate, fatuous. Sometimes they appear forced, added at the last minute to satisfy some perceived literary requirement. Sometimes they can be just plain hilarious. I’ve come across many and I racked my brain for one. Then I remembered Douglas Adams, describing the Vogon ships in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy):

‘The ships hung in the sky in much the same way that bricks don’t.’